| Law | Result |

|---|---|

1908 Root-Takahira Agreement |

“Gentlemen’s Agreement” restricts Japanese |

1917 Immigration Act |

Creation of Asiatic Barred Zone and literacy tests |

1921 Emergency Quota Law |

Quota system favoring northwestern Europeans |

1924 Immigration Act |

Quota system further favoring northwestern Europeans and banning aliens ineligible to citizenship |

Table is abridged and slightly modified. Text is largely the same (see p. 86 of the source material). |

|

Week 2

Early Assimilation Theories

SOCI 231

Lecture I: September 9th

A Vision of Cultural Change

A Quick Reminder

Class Syllabus

The most up-to-date version of our class syllabus will always be available at soci231.netlify.app.

This Week’s Focus—

Robert E. Park’s Early Ideas About Assimilation

Racial Assimilation in Secondary Groups

American Journal of Sociology (1914)

Park’s (1914) Racial Assimilation in Secondary Groups is his first meditation on the meanings, implications and bounds of assimilatory change in America.

The Historical Context

The Historical Context

Only Game in Town?

Was Robert E. Park the only scholar writing about

assimilation at the time?

Only Game in Town?

No.

Only Game in Town?

At the turn of the 20th century, Sarah E. Simons argued—

[A]ssimilation is considered as a process due to prolonged contact. It may, perhaps, be defined as that process of adjustment or accommodation which occurs between the members of two different races, if their contact is prolonged and if the necessary psychic conditions are present. The result is group-homogeneity to a greater or less degree. Figuratively speaking, it is the process by which the aggregation of peoples is changed from a mere mechanical mixture into a chemical compound.

(Simons 1901, 791–92, EMPHASIS ADDED).

Only Game in Town?

As we will see, Park advanced a much different argument in 1914.

Park’s Basic Argument (1914)

Assimilation As Process

There is a process that goes on in society by which individuals spontaneously acquire one another’s language, characteristic attitudes, habits, and modes of behavior. There is also a process by which individuals and groups of individuals are taken over and incorporated into larger groups. Both processes have been concerned in the formation of modern nationalities.

(Park 1914, 606, EMPHASIS ADDED).

Variation Among Cosmopolitans

It has sometimes been assumed that the creation of a national type is the specific function of assimilation and that national solidarity is based upon national homogeneity and “like-mindedness.” The extent and importance of the kind of homogeneity that individuals of the same nationality exhibit have been greatly exaggerated.

(Park 1914, 606, EMPHASIS ADDED).

Variation Among Cosmopolitans

If cosmopolitans truly differ more “in disposition, temperament, and mental capacity” (Park 1914, 607) than their more parochial counterparts, what unites them?

Variation Among Cosmopolitans

The growth of modern states exhibits the progressive merging of smaller, mutually exclusive, into larger and more inclusive social groups.

What one actually finds in cosmopolitan groups, then, is a superficial uniformity, a homogeneity in manners and fashion, associated with relatively profound differences in individual opinions, sentiments, and beliefs.

(Park 1914, 607, EMPHASIS ADDED)

An Example

“In America it has become proverbial that a Pole, Lithuanian, or Norwegian cannot be distinguished, in the second generation, from an American born of native parents” (Park 1914, 607).The Point of Superficial Uniformity

So far as it makes each individual look like every other—no matter how different under the skin—homogeneity mobilizes the individual man. It removes the social taboo, permits the individual to move into strange groups, and thus facilitates new and adventurous contacts.

(Park 1914, 608, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Limits of Inclusion

Park (1914, 610) argued that the main obstacles forestalling assimilation among Black and Asian Americans were

“… not mental but physical traits.”

The Limits of Inclusion

If they were given an opportunity the Japanese are quite as capable as the Italians, the Armenians, or the Slavs of acquiring our culture, and sharing our national ideals. The trouble is not with the Japanese mind but with the Japanese skin. The [Japanese person] is not the right color.

(Park 1914, 610–11, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Implications

“The fact that the Japanese bears in his features a distinctive racial hallmark, that he wears, so to speak, a racial uniform, classifies him. He cannot become a mere individual, indistinguishable in the cosmopolitan mass of the population.” (Park 1914, 611).The Assimilation of Black People in America

From Enslavement to Freedom

The latter half of Park’s (1914) article considers the assimilatory arc of Black Americans—mapping cultural change from the horrors of slavery through to the early 20th century.

Two Americas?

“Gradually, imperceptibly, within the larger world of the white man, a smaller world, the world of the black man, is silently taking form and shape” (Park 1914, 617).

Assimilation of the Subjugated

After a race has achieved in this way its moral independence, assimilation, in the sense of copying, will still continue. Nations and races borrow from those whom they fear as well as from those whom they admire. Materials taken over in this way, however, are inevitably stamped with the individuality of the nationalities that appropriate them.

(Park 1914, 623, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Group Discussion I

Broad Questions

Last week, some of you argued that assimilation is inevitable. Others emphasized the functional utility of assimilating into the mainstream — i.e., to achieve success and stability in a new social world.

Does race complicate these ideas at all? For instance, how can we understand the inevitability and utility of assimilatory change in America in light of the durability of racial disadvantage in the country?

Lecture II: September 11th

Temperature Check

How are things going?

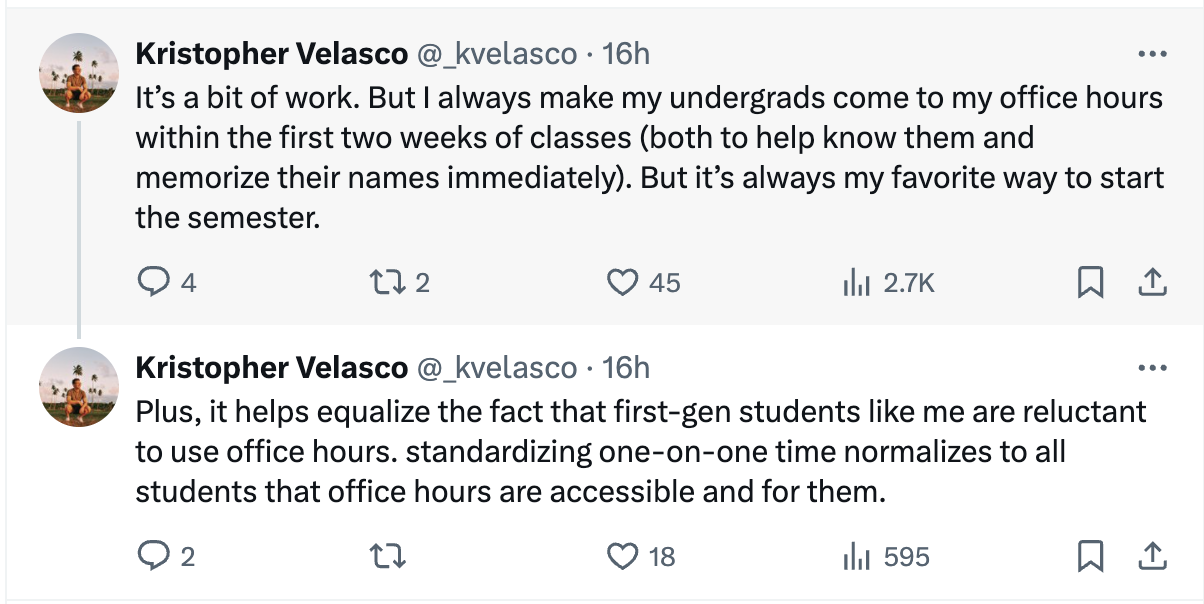

A Note on Office Hours

A Note on Office Hours

Tip

You can schedule a meeting here.

Back to the Future

Briefly Returning to the Present Day

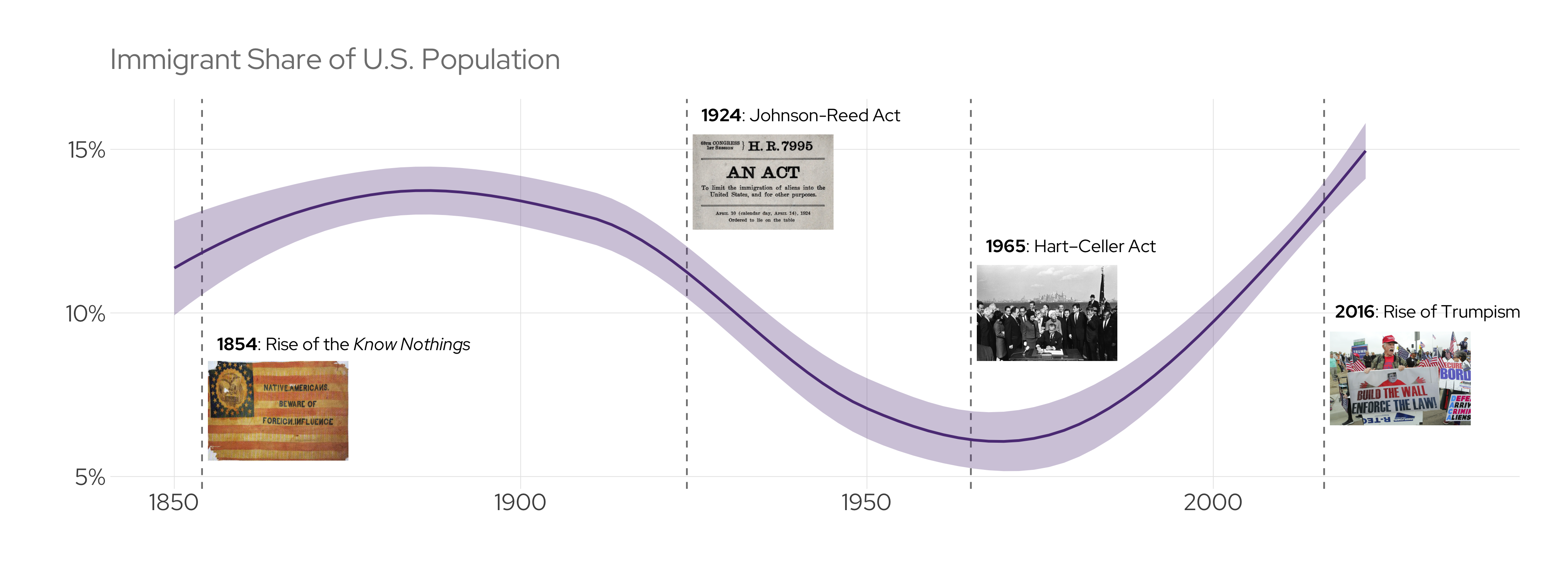

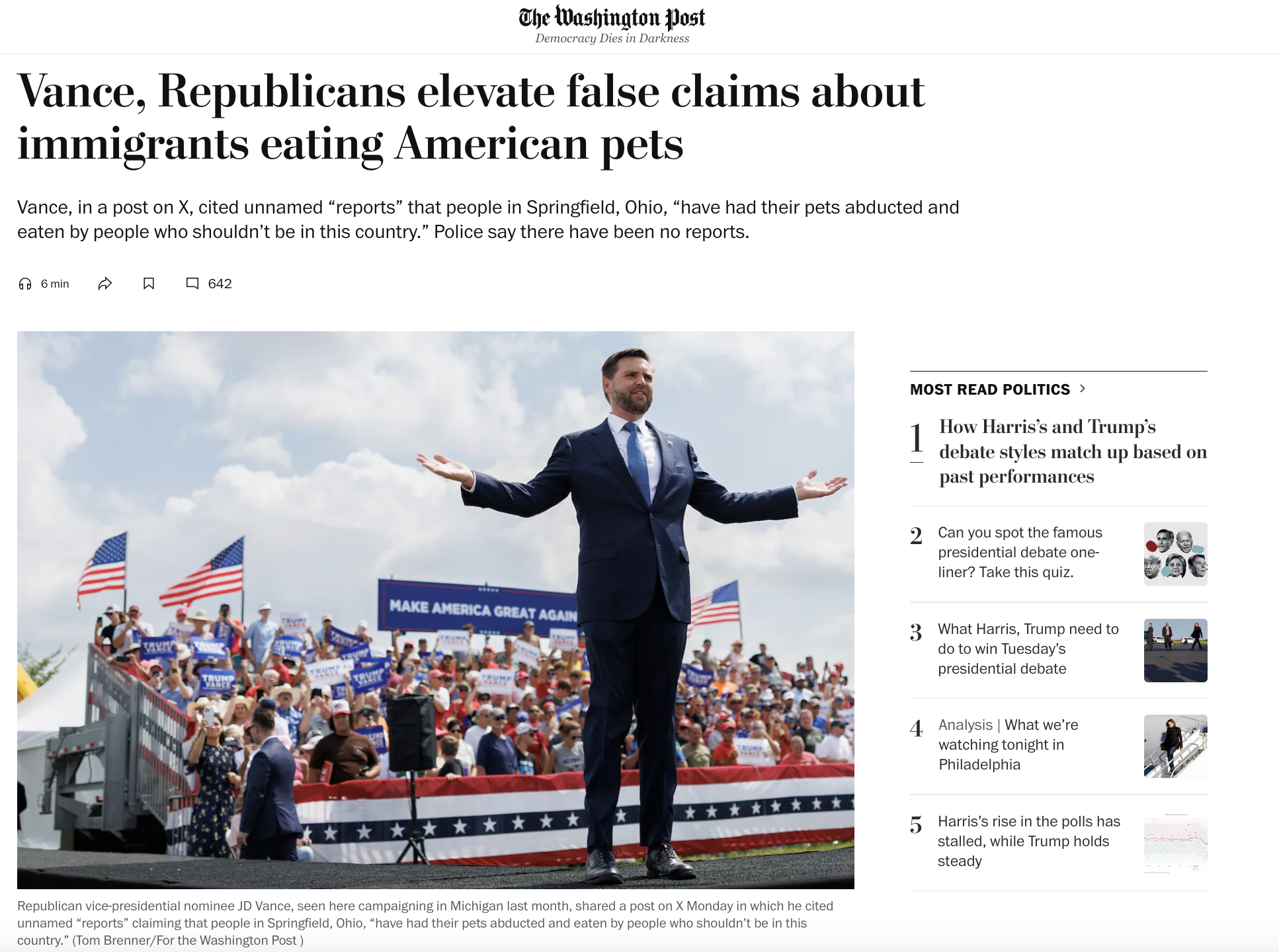

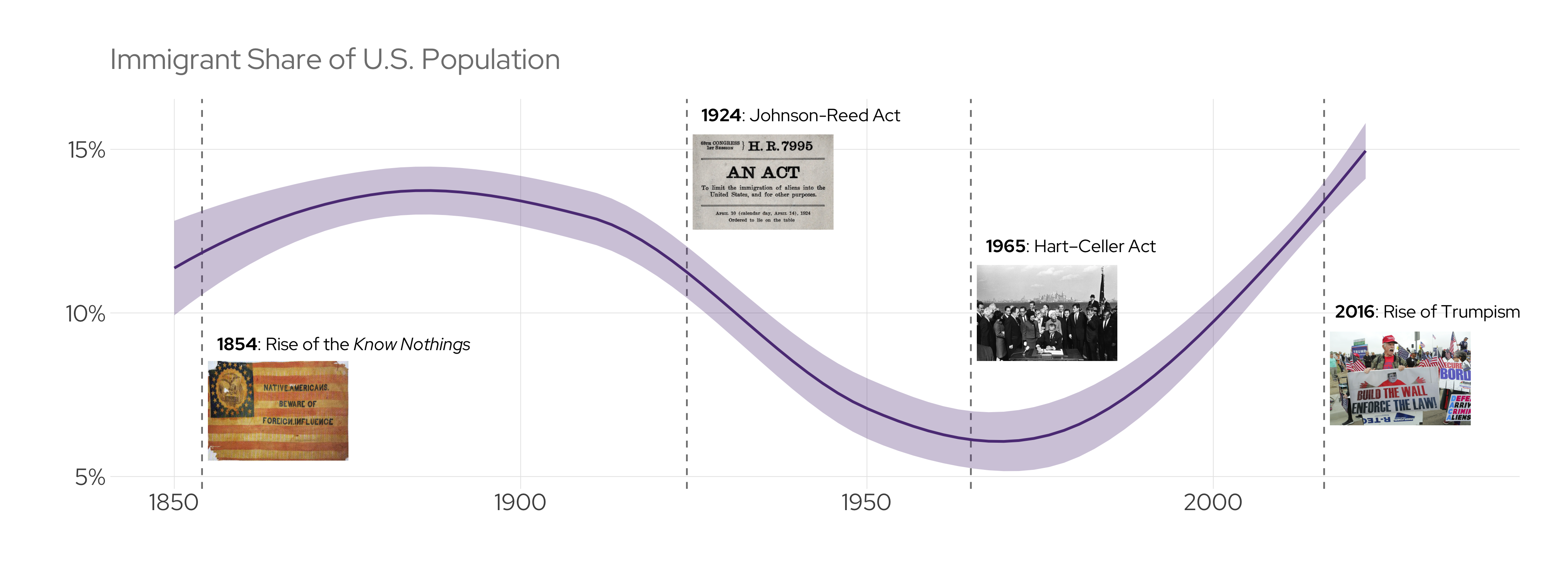

Anti-immigrant sentiment is being mainstreamed once more.

Briefly Returning to the Present Day

Briefly Returning to the Present Day

Briefly Returning to the Present Day

Historical Context (Once Again)

Back to the Past

Introduction to the Science of Sociology

Robert E. Park and E. W. Burgess (1921)

For twenty years after its publication in 1921, Introduction to the Science of Sociology by Robert E. Park and Ernest W. Burgess was the leading textbook in the discipline … As a treatise, it was simultaneously addressed to graduate students throughout the country for whom it became known as the “green bible” as they prepared for their doctoral examinations and research endeavors. Park and Burgess thought of it as a reasoned statement of the theoretical state of the discipline, and they were prepared to have it evaluated as such by mature scholars in the field.

(Janowitz 1969, v, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Chapter XI: Assimilation

Immigration and Americanization

The presence of large groups of foreign-born in the United States was first conceived of as a problem of immigration. From the period of the large Irish immigration to this country in the decades following 1820 each new immigrant group called forth a popular literature of protest against the evils its presence threatened. After 1890 the increasing volume of immigration and the change in the source of the immigrants from northwestern Europe to southeastern Europe intensified the general concern. In 1907 the Congress of the United States created the Immigration Commission to make “full inquiry, examination, and investigation into the subject of immigration.”

(Park and Burgess 1969, 772, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Immigration and Americanization

The European War focused the attention of the country upon the problem of Americanization. The public mind became conscious of the fact that “the stranger within our gates,” whether naturalized or unnaturalized, tended to maintain his loyalty to the land of his origin, even when it seemed to conflict with loyalty to the country of his sojourn or his adoption. A large number of superficial investigations called “surveys” were made of immigrant colonies in the larger cities of the country. Americanization work of many varieties developed apace.

(Park and Burgess 1969, 773, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Defining Assimilation

The concept assimilation, so far as it has been defined in popular usage, gets its meaning from its relation to the problem of immigration. The more concrete and familiar terms are the abstract noun Americanization and the verbs Americanize, Anglicize, Germanize, and the like. All of these words are intended to describe the process by which the culture of a community or a country is transmitted to an adopted citizen. Negatively, assimilation is a process of denationalization and this is, in fact, the form it has taken in Europe.

(Park and Burgess 1969, 734, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Assimilation in Europe and America

The difference between Europe and America, in relation to the problem of cultures, is that in Europe difficulties have arisen from the forcible incorporation of minor cultural groups, i.e., nationalities, within the limits of a larger political unit, i.e., an empire. In America the problem has arisen from the voluntary migration to this country of peoples who have abandoned the political allegiances of the old country and are gradually acquiring the culture of the new.

(Park and Burgess 1969, 734, EMPHASIS ADDED)

A Question

Have these differences persisted? More concretely, does assimilation operate differently in Europe vis-à-vis the United States in the present day?Assimilation in Europe and America

“In both cases the problem has its source in an effort to establish and maintain a political order in a community that has no common culture”

(Park and Burgess 1969, 734).

Three Notions of Assimilation in America

The Magic Crucible

Assimilation, as popularly conceived in the United States, was expressed symbolically some years ago in Zangwill’s dramatic parable of The Melting Pot. William Jennings Bryan has given oratorical expression to the faith in the beneficent outcome of the process: “Great has been the Greek, the Latin, the Slav, the Celt, the Teuton, and the Saxon; but greater than any of these is the American, who combines the virtues of them all.”

(Park and Burgess 1969, 734, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Three Notions of Assimilation in America

Theory of Like-Mindedness

Closely akin to this “magic crucible” notion of assimilation is the theory of “like-mindedness.” This idea was partly a product of Professor Giddings’ theory of sociology, partly an outcome of the popular notion that similarities and homogeneity are identical with unity. The ideal of assimilation was conceived to be that of feeling, thinking, and acting alike.

(Park and Burgess 1969, 735, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Three Notions of Assimilation in America

Interpenetration

Another and a different notion of assimilation or Americanization is based on the conviction that the immigrant has contributed in the past and may be expected in the future to contribute something of his own in temperament, culture, and philosophy of life to the future American civilization. This conception had its origin among the immigrants themselves, and has been formulated and interpreted by persons who are, like residents in social settlements, in close contact with them. This recognition of the diversity in the elements entering into the cultural process is not, of course, inconsistent with the expectation of an ultimate homogeneity of the product. It has called attention, at any rate, to the fact that the process of assimilation is concerned with differences quite as much as with likenesses.

(Park and Burgess 1969, 735, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Sociology of Assimilation

Accommodation vs Assimilation

Accommodation has been described as a process of adjustment, that is, an organization of social relations and attitudes to prevent or to reduce conflict, to control competition, and to maintain a basis of security in the social order for persons and groups of divergent interests and types to carry on together their varied life-activities.

(Park and Burgess 1969, 735, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Sociology of Assimilation

Accommodation vs Assimilation

Assimilation is a process of interpenetration and fusion in which persons and groups acquire the memories, sentiments, and attitudes of other persons or groups, and, by sharing their experience and history, are incorporated with them in a common cultural life. In so far as assimilation denotes this sharing of tradition, this intimate participation in common experiences, assimilation is central in the historical and cultural processes.

(Park and Burgess 1969, 735–36, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Sociology of Assimilation

Accommodation vs Assimilation

An accommodation of a conflict, or an accommodation to a new situation, may take place with rapidity. The more intimate and subtle changes involved in assimilation are more gradual. The changes that occur in accommodation are frequently not only sudden but revolutionary, as in the mutation of attitudes in conversion. The modifications of attitudes in the process of assimilation are not only gradual, but moderate, even if they appear considerable in their accumulation over a long period of time.

(Park and Burgess 1969, 736, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Sociology of Assimilation

Accommodation vs Assimilation

In accommodation the person or the group is generally, though not always, highly conscious of the occasion … [i]n assimilation the process is typically unconscious; the person is incorporated into the common life of the group before he is aware and with little conception of the course of events which brought this incorporation about.

(Park and Burgess 1969, 736, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Sociology of Assimilation

How Assimilation Works (per Park and Burgess)

Assimilation is thus not “the result of conscious reflection, but … the outcome of the unreflective responses to a series of new experiences” (Park and Burgess 1969, 736).

A Question

How might this happen?The Sociology of Assimilation

How Assimilation Works (per Park and Burgess)

The intimate associations of the family and of the play group, participation in the ceremonies of religious worship and in the celebrations of national holidays, all these activities transmit to the immigrant and to the alien a store of memories and sentiments common to the native-born, and these memories are the basis of all that is peculiar and sacred in our cultural life.

(Park and Burgess 1969, 736, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Sociology of Assimilation

How Assimilation Works (per Park and Burgess)

Through the mechanisms of imitation and suggestion, communication effects a gradual and unconscious modification of the attitudes and sentiments of the members of the group. The unity thus achieved is not necessarily or even normally like-mindedness; it is rather a unity of experience and of orientation, out of which may develop a community of purpose and action.

(Park and Burgess 1969, 736, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Important Conditions

- Primary Contacts

- Common Language

Group Discussion II

Summarizing Park’s Theory of Assimilation

How would you summarize Park’s ideas about assimilation?

In groups of 2-3, take some time to revisit your notes and arrive at a high-level summary.

Then, offer some criticism.

What is missing in Park’s vision of assimilatory change? What are, in your view, some potential paths forward? For some inspiration, feel free to return to Hirsch’s (1942) essay in Social Forces.

Enjoy the Weekend

References